It was during the Civil War that soldiers first found the need for some kind of identification on their bodies during combat.

According to the National Museum of Naval Aviation:

“In the days of the Civil War, 1861-1865, some soldiers going into combat improvised their own identification, pinning slips of paper with name and home address to the backs of their coats, stenciling identification on their knapsacks or scratching it in the soft lead backing of the Army belt buckle.”

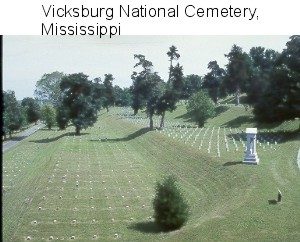

Record keeping was haphazard under wartime conditions and grave locations were often lost. After the conclusion of the Civil War the U.S. Army located and exhumed the remains of 300,000 Union veterans buried in the South, then reinterred these remains in a national cemetery. Nationwide, 54% of the number reinterred were classified as “Unknown”. At Vicksburg National Cemetery 75% of the Civil War dead are listed as unidentified. At Salisbury National Cemetery, North Carolina, 99% of the 12,126 Federal soldiers interred are listed as unidentified.

The first national cemeteries were established in 1862 by an act of Congress to provide a burial place for “soldiers who shall die in the service of the country”. Upright headstones with rounded tops mark the graves of known soldiers. Small, square blocks, incised with a grave number only, designate the unknown veterans. A few graves are marked by other than government issued headstones.

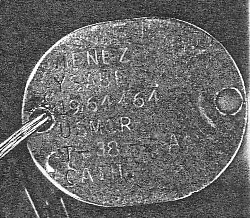

From 1862 to 1906, many systems of identification were presented to the government for adoption and publicly for individual sale. Then in 1906 a circular aluminum disc was presented and by 1913 identification tags were made mandatory.

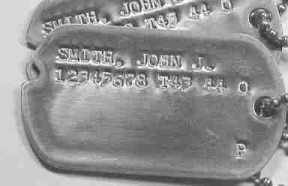

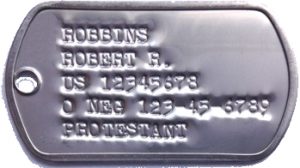

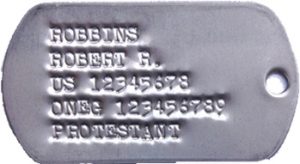

From 1862 to 1906, many systems of identification were presented to the government for adoption and publicly for individual sale. Then in 1906 a circular aluminum disc was presented and by 1913 identification tags were made mandatory. During WWII the circular, engraved disk (shown above) was replaced by the rectangular shaped dog tag with a Notch. The nickname “dog tags” was adopted during WWII. The dog tags on the right, are shown without silencers. Silencers were put in use around the end of 1944.

During WWII the circular, engraved disk (shown above) was replaced by the rectangular shaped dog tag with a Notch. The nickname “dog tags” was adopted during WWII. The dog tags on the right, are shown without silencers. Silencers were put in use around the end of 1944.Those who never received silencers may have looked for their own solutions by sticking the tags together with cotton ties, rubber rings from gas-mask tubes, and/or adhesive tape.

The Tomb of the Unknowns Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, USA “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY AN AMERICAN SOLDIER KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

The Tomb of the Unknowns Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, USA “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY AN AMERICAN SOLDIER KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

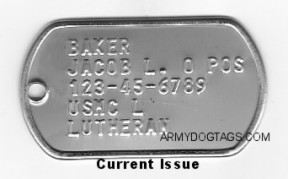

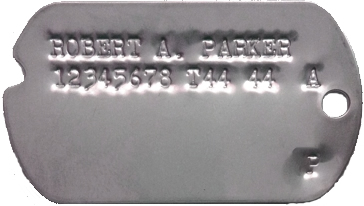

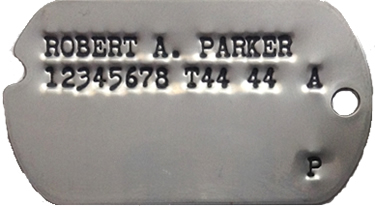

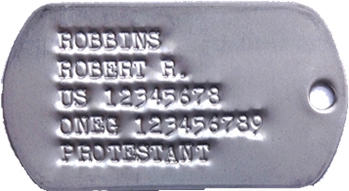

During the late 1950s the Notched dog tag was discontinued and replaced with the tag that is used today—without a notch. Also, the second tag was separated from the first tag by placing it on its own short chain, 5.5″. If a soldier is killed in combat, the tag on the short chain would be placed on the soldier’s toe for identification. Thus, coming to be known as the “toe tag”.

During the late 1950s the Notched dog tag was discontinued and replaced with the tag that is used today—without a notch. Also, the second tag was separated from the first tag by placing it on its own short chain, 5.5″. If a soldier is killed in combat, the tag on the short chain would be placed on the soldier’s toe for identification. Thus, coming to be known as the “toe tag”.

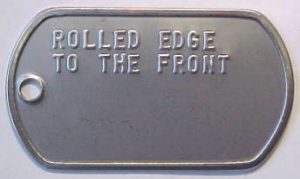

Rolled Edge to Front (the rolled edge can be seen when reading the text) is how we usually stamp Current Issue dog tags.

Rolled Edge to Front (the rolled edge can be seen when reading the text) is how we usually stamp Current Issue dog tags.

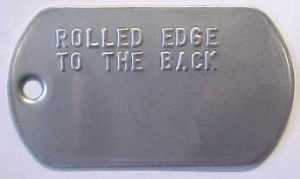

WWII and Korea era dog tags were stamped with the rolled edge to the back (the rolled edge can not be seen when reading the text).

WWII and Korea era dog tags were stamped with the rolled edge to the back (the rolled edge can not be seen when reading the text).